The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season comes to an end Thursday. Reviews are decidedly mixed.

It was quite an unusual season from a meteorological standpoint, hyperactive and at the same time ordinary. More on that later. But from an impacts point of view, there were some sadly significant events.

Watch NBC6 free wherever you are

>2023’s Most Impactful Storms

Tropical activity in the Atlantic began in January, not June, when an unnamed subtropical storm formed a couple of hundred miles off the coast of North Carolina and moved towards the Canadian maritime provinces.

Get local news you need to know to start your day with NBC 6's News Headlines newsletter.

>That system served as an inadequate warmup for the storm that would hit the same region in September, when the post-tropical remnant of Hurricane Lee hit Nova Scotia and New Brunswick bringing damage and power outages to the region. Lee’s remnant also impacted the state of Maine.

Lee is perhaps best remembered for its rapid intensification. At 5 a.m. on September 7 it had 80 mph winds. By 11 p.m that night Lee had become a 160 mph category 5 monster.

JOHN MORALES ON HURRICANES

Rapid intensification cycles are manifesting themselves more frequently due to climate change, leading to a greater proportion of tropical storms reaching potentially catastrophic category 4 and 5 status.

Jumping back to June, the Windward Islands got hit by Tropical Storm Bret. Spurred by the record hot sea surface temperatures observed all season long in the Atlantic, Bret was only the eight June tropical storm to form in the Main Development Region (MDR) of the Atlantic west of Africa since records began in 1851.

As if that wasn’t unusual enough, Tropical Storm Cindy also formed east of the Lesser Antilles towards the end of the month.

In August, Tropical Storm Franklin brought 13 inches of rain to parts of the Dominican Republic, displacing families and causing fatalities. Once over the Atlantic, Franklin gained hurricane status and rapidly intensified from a category 1 to a category 4 in 24 hours. Thankfully it missed Bermuda by several hundred miles.

One August tropical storm caused more good than harm. Tropical Storm Harold brought heavy rain (and some floods) to drought-stricken South Texas on August 22. The storm that followed, though, was very harmful for Florida.

Hurricane Idalia fed off of the hot waters of the Gulf of Mexico and went from a category 1 to a category 4 hurricane in just 24 hours, in another episode of rapid intensification.

While it thankfully lost a little strength prior to landfall in Florida’s Big Bend region, the damage from the 125 mph major hurricane was substantial. Small coastal communities were severely crippled by a storm surge as deep as 12 feet, as winds and tornadoes leveled trees, power lines, and weaker structures further inland. Preliminary damage estimates have been in the $2.5 billion range.

Late season systems impacted the Caribbean. Tropical Storm Phillipe had a slight impact on the Leeward Islands in September. Then Hurricane Tammy grazed a good chunk of the Lesser Antilles in October, producing moderate wind and flood damage.

Then, towards the tail end of the season in mid-November, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) tagged a disturbance in the western Caribbean as a potential tropical cyclone. While the system never organized sufficiently to become a tropical depression or storm, it produced major damage in Hispaniola. Over two dozen deaths were recorded, mainly in the Dominican Republic, as nearly 20 inches of rain accumulated during a two-day stretch.

This Season’s Conflicting Signals

The record hot Atlantic Ocean played a huge role in fostering the development of a large number of storms—21 in total versus the annual average of 14. It also triggered scary-fast rapid intensification in Franklin, Idalia, and Lee. But each 2023 storm behaved in drastically different ways depending on another crucial environmental factor: upper level wind shear.

The developing El Niño in the Pacific Ocean managed to produce enough days with strong westerly winds aloft across the Atlantic basin to keep many tropical storms from reaching hurricane strength. Out of the 21 storms, only 7 achieved winds of 75 mph or greater.

That ratio of 33 percent is much lower than the norm. Typically, 1 of every 2 storms attains hurricane status. While record-hot waters produced many more Atlantic storms than one would expect in an El Niño year, it is wrong to state that we saw no benefit at all from the phenomenon.

Because only Harold (Texas), Idalia (Florida), and a very weak Tropical Storm Ophelia (North Carolina) made landfall in the U.S. this year, there’s a general perception, purely from the American point of view, that the season was quiet. South Florida managed to avoid being placed in an NHC forecast “cone” for the first time since 2014! But accounting for overall storm strength and longevity, the 2023 Atlantic season ended up being 20% more active than normal. If not for the El Niño, it could’ve been much, much worse.

It also could’ve been much worse for the United States if the steering currents hadn’t set up the way they did this year. A short-term climatic variation known as the Atlantic Oscillation (AO) spent a good portion of hurricane season in its negative phase. When the AO is negative, the Bermuda high is weaker, dips in the jet stream frequent the Eastern Seaboard and western Atlantic, and cold fronts dive south towards the equator with greater frequency.

That means that the vast majority of tropical storms and hurricanes this season were steered northbound well before threatening the U.S. That is especially true for hurricanes originating in the waters west of Africa—historically the strongest and costliest ones. It’s not far-fetched to envision category 5 Hurricane Lee heading somewhere between Florida and Long Island had it not been for that big deflector shield set up by the Atlantic Oscillation this year.

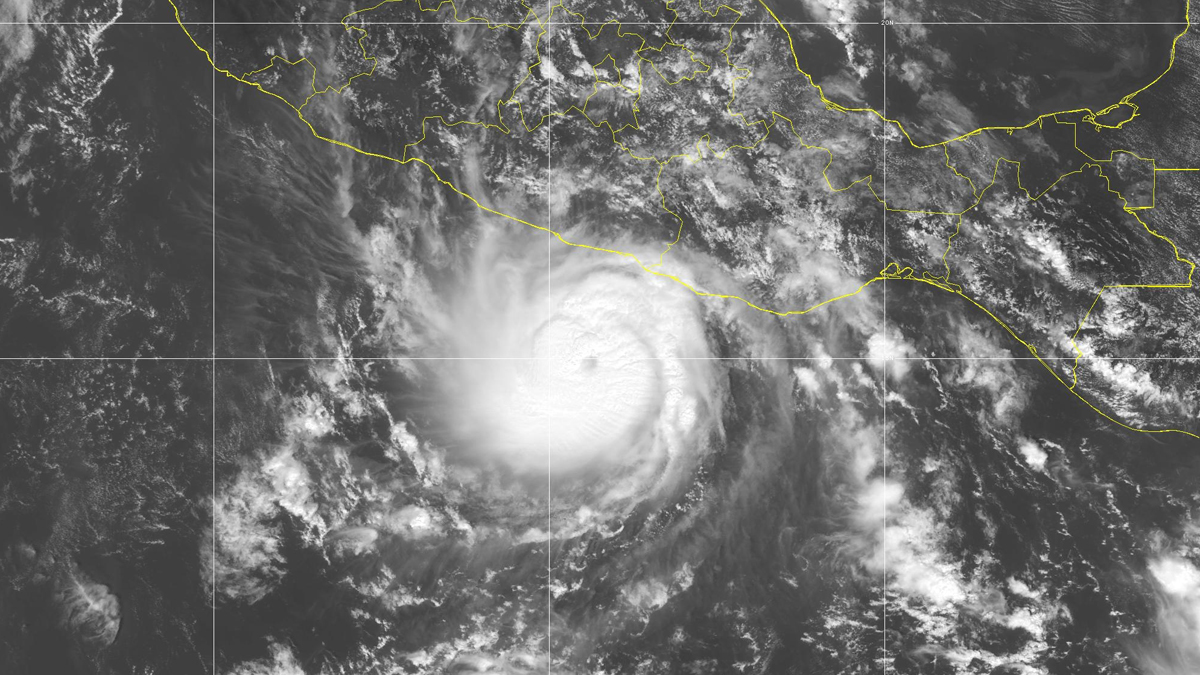

In summary, given the troublesome trends brought on by the warming climate, 2023’s Atlantic hurricane season could’ve been much worse. Just look at the eastern Pacific, where an incredible 80% of this year’s storms underwent rapid intensification, culminating in Otis’ devastating category 5 hit on Acapulco, Mexico.

Thanks to El Niño’s wind shear and the Atlantic Oscillation’s steering currents, the U.S. got off easy.

John Morales is NBC6's hurricane specialist.