I know that over the decades you’ve come to know me as a non-alarmist. I try not to worry you when there’s no need to worry. But what’s been happening lately cannot be sugarcoated.

This is a scary new paradigm in the tropics. And we all need to worry.

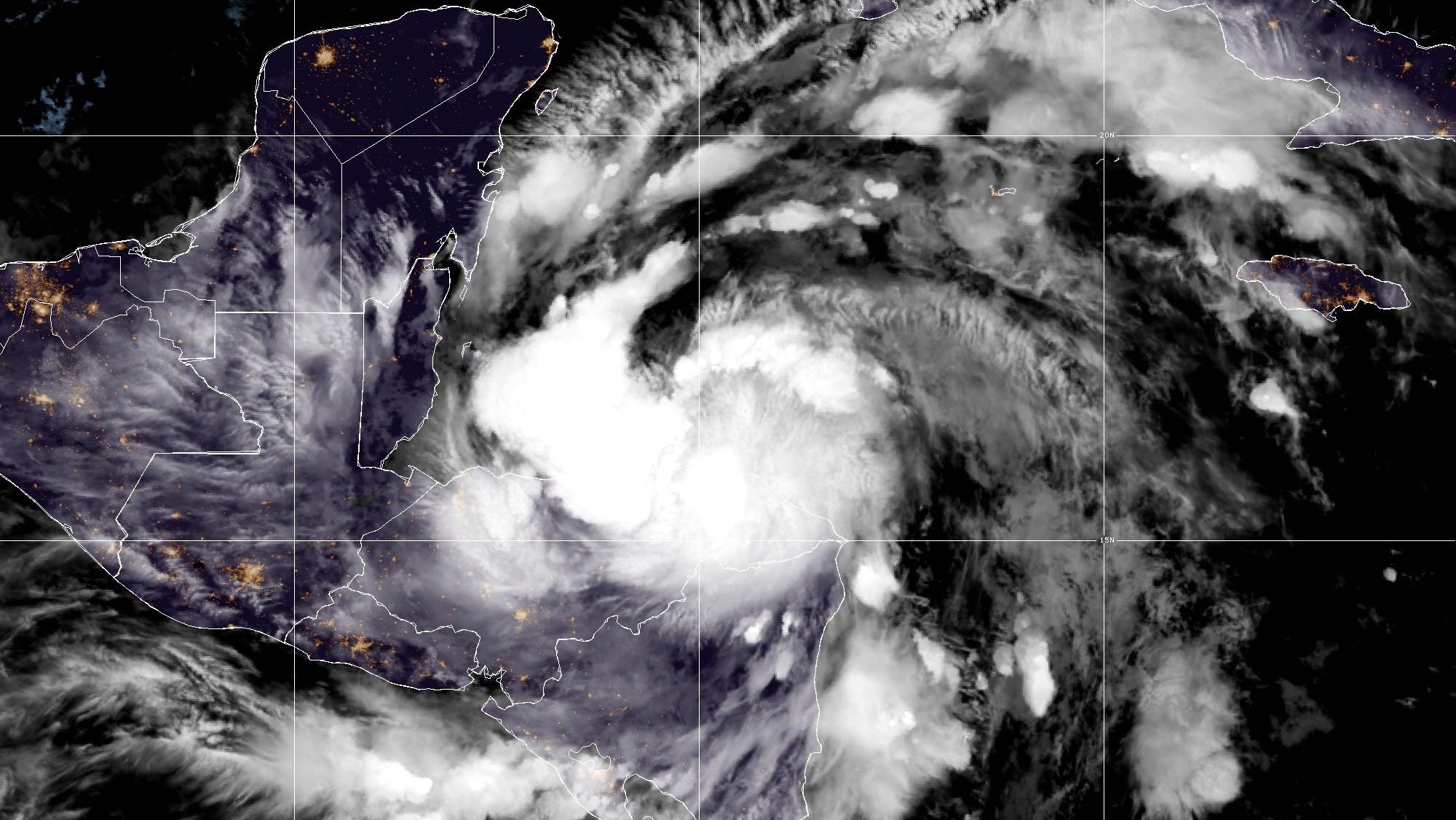

Hurricane Otis struck very near Acapulco, Mexico, on Tuesday night as a monster 165 mile-per-hour category 5 cyclone. On Monday night, about 24-hours prior to landfall, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) was predicting it would do so as 70 mile-per-hour tropical storm.

With the energy content (and destructive potential) of the wind increasing with the cube of the windspeed, that means that Otis reached Mexico with 13 times more destructive potential than what had been called for! Even when the tardy hurricane warning was issued at 4 a.m. local time on Tuesday, NHC was still forecasting just an ordinary category 1 hurricane to reach Mexico’s Pacific coast.

The Hurricane season is on. Our meteorologists are ready. Sign up for the NBC 6 Weather newsletter to get the latest forecast in your inbox.

I want to be clear that this is not an article about NHC’s skill. The collection of experts at their offices in Miami is the best in the hemisphere at analyzing and forecasting tropical cyclones. I’ve written about how they were once hesitant to forecast rapid intensification of hurricanes but have adjusted do so more often‚ like they correctly did for hurricanes Idalia and Lee in the Atlantic this year.

In the case of Otis, NHC first noted in their Sunday advisories that the waters were "very warm." Rapid intensification was first contemplated late on Monday night based on the low-level structure of the tropical storm at the time. On Tuesday morning NHC indicated that models showed a 1-in-4 chance of Otis undergoing rapid intensification (RI), and by midday the chance of RI was characterized as "greater than normal." But RI was never explicitly called for.

Otis then proceeded to go from a 50 mph low-end tropical storm at 11 p.m. on Monday night to a 160 mph category 5 hurricane 24 hours later. Just on Tuesday afternoon, Otis grew from a tropical storm into a category 3 hurricane in the span of six hours! Otis' level of rapid intensification broke Hurricane Patricia’s record in 2015 for fastest-strengthening hurricane in a span of 12 hours eastern Pacific.

While Otis is a record-setter, this is far from the first time the eastern Pacific has seen rapidly intensifying hurricanes this year. A whopping 80% of this year’s storms have undergone rapid intensification. Norma did it just before Otis, and Lidia earlier this month went from 80 to 140 mph in just 18 hours. Jova, in September, went from 70 to 155 mph in a day.

Hurricane Season

The NBC 6 First Alert Weather team guides you through hurricane season

The Atlantic, which has faced El Niño-produced wind shear often, still has had three hurricanes undergo RI in 2023: Franklin, Idalia (which struck Florida), and Lee, which reached the once-rare category 5 intensity. In the western Pacific, nearly half of all storms underwent RI.

For those of you that follow developments in climate science, you’ve known that for many years the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had been predicting that tropical cyclone intensities would increase in a warming climate. Confidence in that forecast has gone from medium to high over the years. And while the total number of tropical storms around the globe has remained steady, the proportion of those reaching category 4 & 5 intensity had indeed gone up.

Which leads to my warning.

I am supremely confident forecasting hurricane tracks. If it’s not coming, it’s not coming! But I am no longer as comfortable in putting everyone at ease in regard to the strength of a storm. My confidence in forecasting storm intensity is decreasing.

In the battle of wind shear versus hot sea surface temperatures, it seems like the warm water is winning most of the time. Otis had wind shear over it, and it didn’t matter.

One of these days, in the not too distant future, there’s going to be a run-of-the-mill tropical storm in the central Bahamas that’s going to ramp up to category 4 or 5 intensity before reaching Miami. Will NHC or I be able to correctly call for such rapid intensification?

If they can miss it, so can I.

All that to say that we are in a new era, one in which climate change, through the physical changes it’s producing in the ocean and atmosphere, is boosting windspeeds and rainfall in hurricanes. The insurers and reinsurers see it, and it’s reflected in their premiums. The military sees it, and it’s reflected in the actions they’re taking to retrofit bases and prepare for climate-driven crises. And 3 in 4 Americans see it, and it’s manifesting in how the climate crisis is ticking up in the rankings of the most important voter priorities.

This hurricane season will be over in a month or so, and obviously we’ll be watchful. But I want you to think of future hurricane seasons and this scary new paradigm. There are limits to resiliency, but preparedness has never been more important.

Future hurricanes are more likely than ever to be worse than any you’ve ever experienced.

John Morales is NBC6's hurricane specialist.