Category 5 hurricanes used to be rare.

Used to be.

Watch NBC6 free wherever you are

>When Hurricane Lee’s barometric pressure went off a cliff on Thursday, dropping an astonishing 61 millibars in 18 hours, winds jumped from a relatively modest 80 miles per hour in the early morning to 160 mph by evening. Some surprised lay observers commented on social media that Lee had “jumped over” several categories, straight to a Category 5.

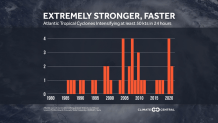

Lee indeed is the first Atlantic Cat 5 of 2023, but this hurricane is just one of eight tropical cyclones to attain this ill-famed intensity in the Atlantic over the past eight years. Since the beginning of the century, 16 Category 5 hurricanes have formed in the Atlantic—a rate slightly higher than one every year-and-a-half.

Get local news you need to know to start your day with NBC 6's News Headlines newsletter.

>In contrast, from 1970 to 2000 only six Atlantic systems were able to reach Cat 5. That was a rate of 1 every 5 years. That means that the frequency of category 5’s has tripled compared to those last 3 decades of the 20th century. Going much further back to 1924, only 6% of hurricanes had been able to reach that extreme strength.

It’s not just the Atlantic. Hurricane Jova in the eastern Pacific was a Cat 5 this week. The Australian region had two Category 5 cyclones earlier this year, and another in December 2022. Also in 2022, the West Pacific had two Super Typhoons reach that maximum category.

More storms reaching category 5 intensity is not to be confused with a higher overall count of tropical cyclones. It is incorrect to say that the planet is experiencing more active—in terms of named systems—hurricane, typhoon, and cyclone seasons. Scientists never have predicted a greater number of tropical storms due to any of the changes in climate that we’ve been experiencing.

What we are seeing is that a greater proportion of the tropical storms that do form are going through rapid intensification cycles that often result in hurricanes becoming potentially catastrophic category 4 and 5 systems. It’s not hard to figure out why: global heating.

Tropical disturbances feed off of warm water. The temperature of the surface of the ocean generally needs to be above 80 degrees Fahrenheit for storms to prosper. Once a hurricane forms, the ease at which its winds can evaporate water and lift it in gaseous form until it cools and condenses is enhanced if it’s moving over hotter water. When water vapor condenses back into liquid form, energy is released into the hurricane which strengthens it further. For every 1 degree Fahrenheit increase in water temperature, potential storm intensity can increase by 10%.

Given the record Atlantic marine heatwave unleashed during the hottest northern hemisphere summer ever recorded on the planet, perhaps a Cat 5 should’ve been considered fait accompli.

Despite these concerning trends, the one good thing about Lee is that it’s unlikely to impact any land mass while it’s at its peak intensity, which may have already passed. What happens next week once it’s moving north across the western Atlantic is still unknown, but Lee is being closely watched from New England to Canada to Bermuda.