Last year, Hurricane Otis struck very near Acapulco, Mexico, as a monster 165 mile-per-hour category 5 cyclone. About 24-hours before landfall, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) was predicting it would do so as 70 mile-per-hour tropical storm.

With the energy content (and destructive potential) of the wind increasing with the cube of the windspeed, that means that Otis reached Mexico with 13 times more destructive potential than what had been expected!

Watch NBC6 free wherever you are

Even when the hurricane warning was issued, the hurricane center was still forecasting just an ordinary category 1 hurricane to reach Mexico’s Pacific coast.

For a region of Mexico that had never experienced anything stronger than a category 1, getting hit by a cat-5 with little to no warning led to severe consequences.

Get local news you need to know to start your day with NBC 6's News Headlines newsletter.

Less than a year later, Hurricane Helene became a major hurricane on September 26th amid a rapid intensification (RI) cycle in which it attained 55 mph greater windspeeds in a span of 24-hours—just short of the “extreme” RI threshold of 58 mph in 24 hours.

It was the second time since it formed that maximum sustained windspeeds had increased by at least 35 miles per hour in a day.

As a result, Helene went from an 80-mph low-end Category 1 hurricane one day to a 140 mph Category 4 cyclone the next. According to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, Category 1 hurricane damage would be expected to be “minimal,” while Category 4 hurricane damage would be “devastating.”

Hurricane Season

The NBC 6 First Alert Weather team guides you through hurricane season

Warming oceans are fueling stronger tropical cyclones—the costliest weather disasters in the United States.

Helene’s intensity took off while passing over waters that were over 3 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than historical averages, a condition made 600 times more likely by climate change, according to Climate Central’s CSI Ocean index.

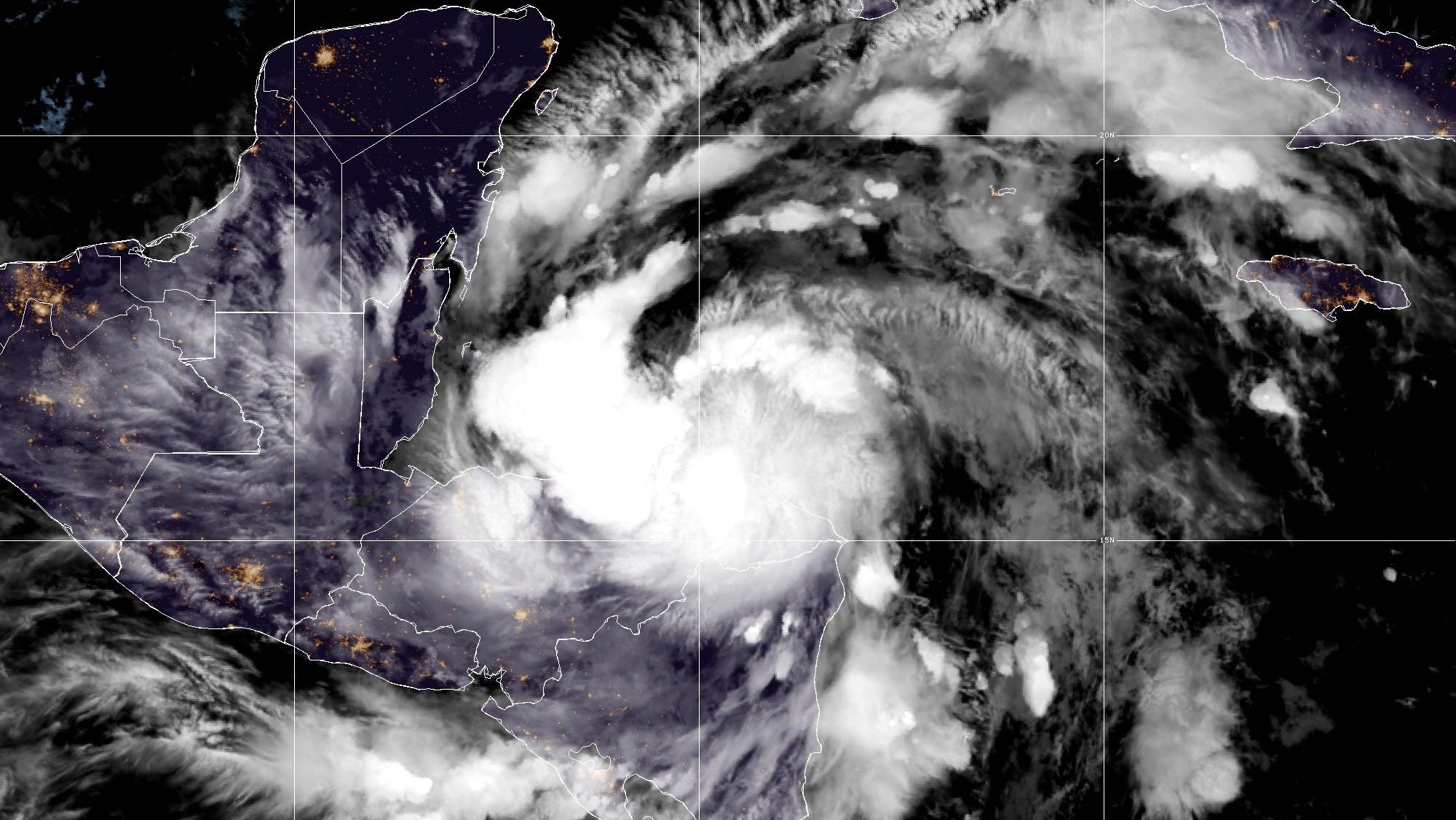

And now for Hurricane Milton, extreme-RI has been attained. A mundane tropical storm with 50 mph winds on Sunday morning became a monstrous 180 mph Category 5 hurricane 36 hours later.

1️⃣7️⃣5️⃣ mph 📈

— John Morales (@JohnMoralesTV) October 7, 2024

9️⃣1️⃣1️⃣ mb 📉

Truly horrific pic.twitter.com/sZkeyRlr7m

Sea surface temperatures in the region where Hurricane Milton is developing are at or above record-breaking highs. A rapid attribution analysis determined that those temperatures were made up to 400-800 times more likely by climate change over the past two weeks.

After skirting the north coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, Milton is expected to slightly weaken and make landfall in Florida late on Wednesday evening.

Since 2017, eight Category 4 and 5 hurricanes have struck U.S. soil—as many Cat 4 & 5 landfalls as occurred in the previous 57 years.

This concerning recent trend fits overall tendencies in the Atlantic. Observations show an increase in tropical cyclone intensification rates in the Atlantic basin from 1982-2009. The number of storms that quickly intensified from Category 1 (or weaker) into a major hurricane more than doubled in 2001-2020 compared to 1971-1990.

Globally, the proportion of tropical cyclones that reach very intense (Category 4 and 5) levels is projected to increase, too.