Venezuelans are voting Sunday in a presidential election whose outcome will either lead to a seismic shift in politics or extend by six more years the policies that caused the world’s worst peacetime economic collapse.

Whether it is President Nicolás Maduro who is chosen, or his main opponent, retired diplomat Edmundo González, the election will have ripple effects throughout the Americas. Government opponents and supporters alike have signaled their interest in joining the exodus of 7.7 million Venezuelans who have already left their homes for opportunities abroad should Maduro win another term.

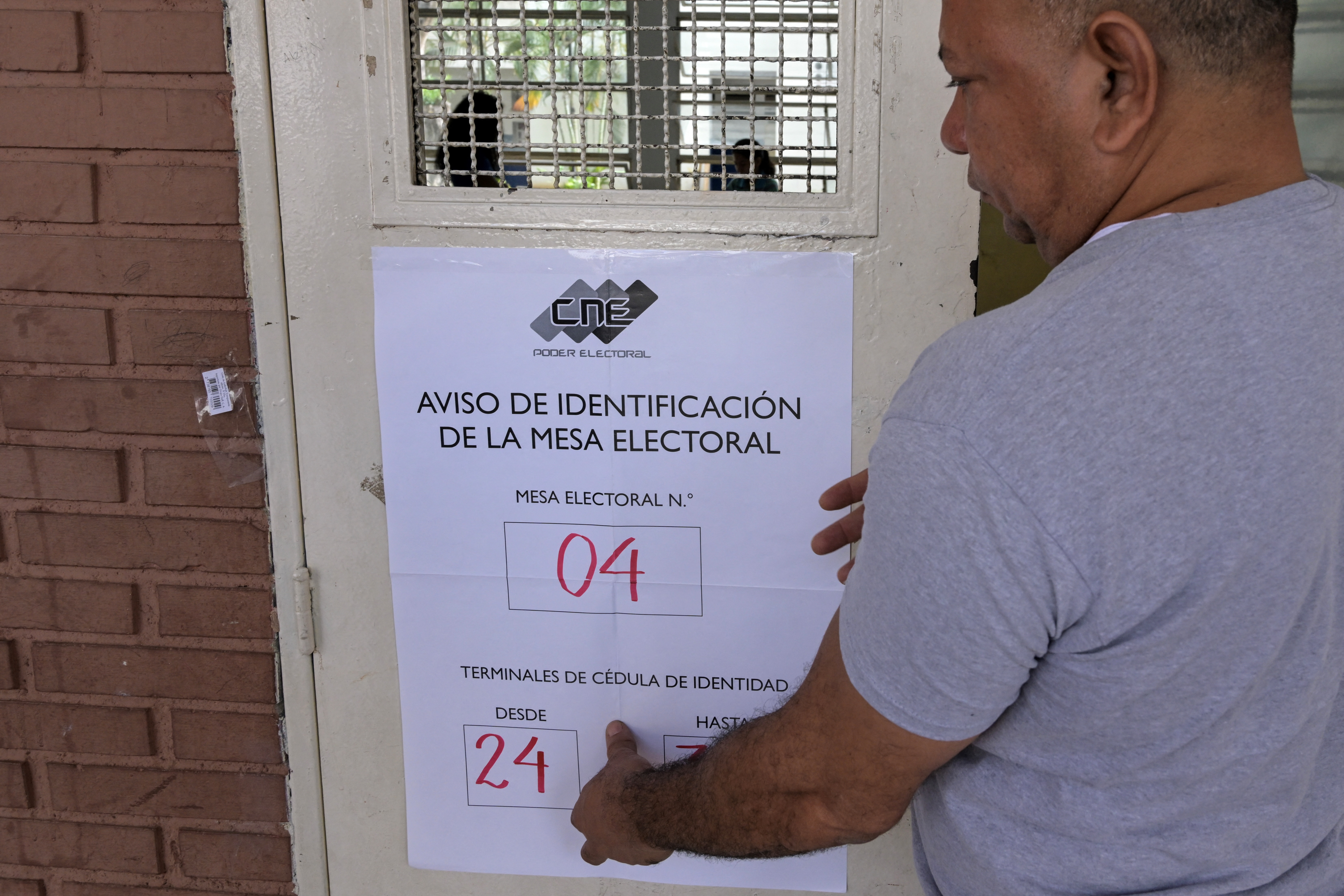

Polls opened at 6 a.m., but voters started lining up at some voting centers across the country much earlier, sharing water, coffee and snacks for several hours.

Alejandro Sulbarán snagged the first spot at his voting center by getting in line at 5 p.m. Saturday. He said he stood outside an elementary school in a hillside suburb of the capital, Caracas, for “the future of the country.”

The Hurricane season is on. Our meteorologists are ready. Sign up for the NBC 6 Weather newsletter to get the latest forecast in your inbox.

“We are all here for the change we want," Sulbarán, 74, who runs a maintenance business, said as other voters nodded in agreement.

The number of eligible voters for this presidential election is estimated to be around 17 million. Polls will close at 6 p.m. local time, but it was unclear when electoral authorities will release the first results.

Authorities set Sunday's election to coincide with what would have been the 70th birthday of former President Hugo Chávez, the revered leftist firebrand who died of cancer in 2013, leaving his Bolivarian revolution in the hands of Maduro. But Maduro and his United Socialist Party of Venezuela are more unpopular than ever among many voters who blame his policies for crushing wages, spurring hunger, crippling the oil industry and separating families due to migration.

More news on Venezuela's election

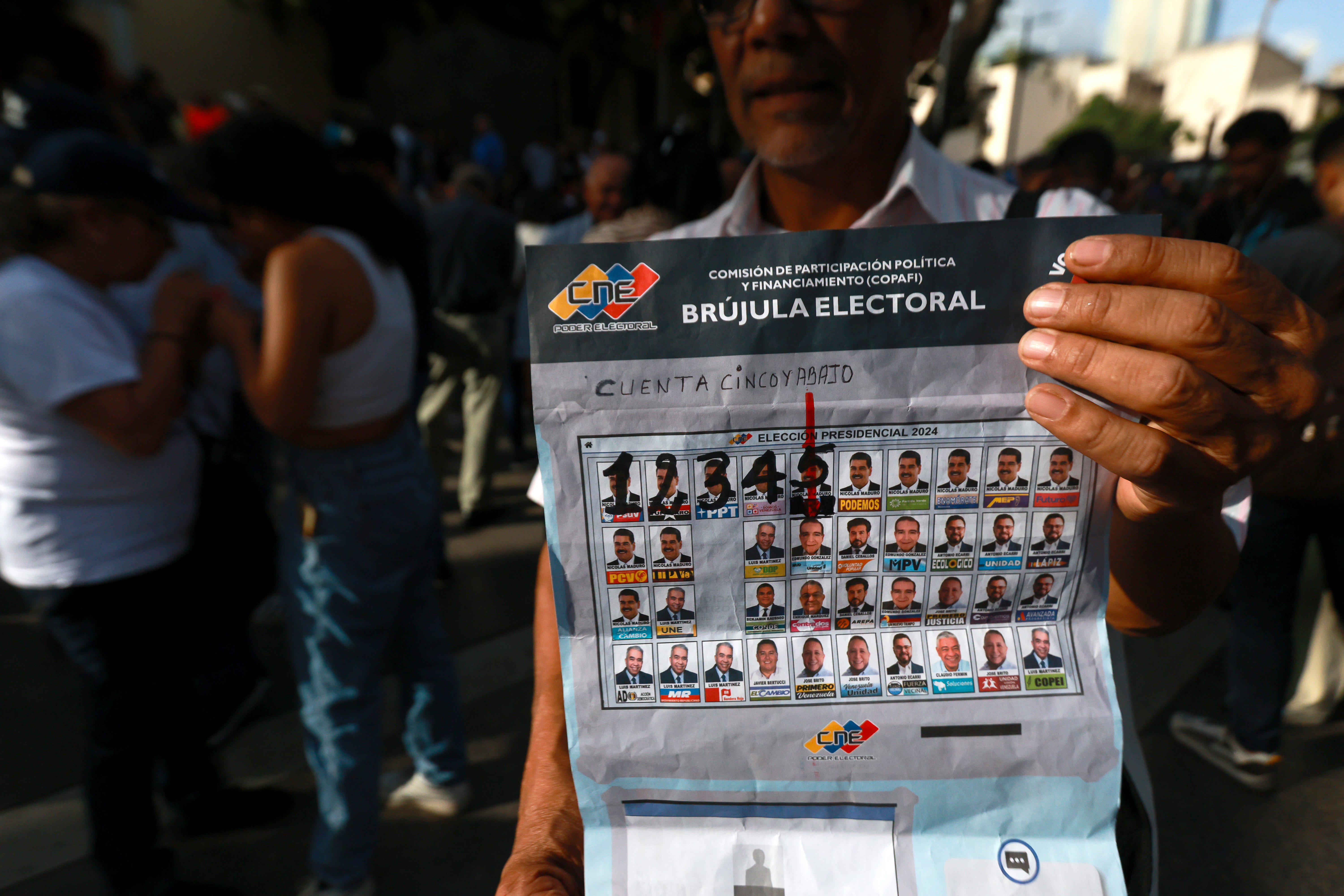

Maduro, 61, is facing off against an opposition that has managed to line up behind a single candidate after years of intraparty divisions and election boycotts that torpedoed their ambitions to topple the ruling party.

González is representing a coalition of opposition parties after being selected in April as a last-minute stand-in for opposition powerhouse Maria Corina Machado, who was blocked by the Maduro-controlled Supreme Tribunal of Justice from running for any office for 15 years.

Machado, a former lawmaker, swept the opposition's October primary with over 90% of the vote. After she was blocked from joining the presidential race, she chose a college professor as her substitute on the ballot, but the National Electoral Council also barred her from registering. That's when González, a political newcomer, was chosen.

Sunday's ballot also features eight other candidates challenging Maduro, but only González threatens Maduro's rule.

After voting, Maduro said he would recognize the election result and urged all other candidates to publicly declare that they would do the same.

“No one is going to create chaos in Venezuela,” Maduro said. “I recognize and will recognize the electoral referee, the official announcements and I will make sure they are recognized.”

Venezuela sits atop the world's largest proven oil reserves, and once boasted Latin America's most advanced economy. But it entered into a free fall after Maduro took the helm. Plummeting oil prices, widespread shortages and hyperinflation that soared past 130,000% led first to social unrest and then mass emigration.

Economic sanctions from U.S. seeking to force Maduro from power after his 2018 reelection — which the U.S. and dozens of other countries condemned as illegitimate — only deepened the crisis.

Maduro's pitch to voters this election is one of economic security, which he tried to sell with stories of entrepreneurship and references to a stable currency exchange and lower inflation rates. The International Monetary Fund forecasts the economy will grow 4% this year — one of the fastest in Latin America — after having shrunk 71% from 2012 to 2020.

But most Venezuelans have not seen any improvement in their quality of life. Many earn under $200 a month, which means families struggle to afford essential items. Some work second and third jobs. A basket of basic staples — sufficient to feed of family of four for a month — costs an estimated $385.

Judith Cantilla, 52, voted to change those conditions.

“For me, change in Venezuela (is) that there are jobs, that there’s security, there’s medicine in the hospitals, good pay for the teachers, for the doctors,” she said, casting her ballot in the working-class Petare neighborhood of Caracas.

Elsewhere, Liana Ibarra, a manicurist in greater Caracas, got in line at 3 a.m. Sunday with her water, coffee and cassava snack-laden backpack only to find at least 150 people ahead of her.

“There used to be a lot of indifference toward elections, but not anymore,” Ibarra said.

She said that if González loses, she will ask her relatives living in the U.S. to sponsor her and her son's application to legally emigrate there. “We can’t take it anymore,” she said.

The opposition has tried to seize on the huge inequities arising from the crisis, during which Venezuelans abandoned their country's currency, the bolivar, for the U.S. dollar.

González and Machado focused much of their campaigning on Venezuela’s vast hinterland, where the economic activity seen in Caracas in recent years didn't materialize. They promised a government that would create sufficient jobs to attract Venezuelans living abroad to return home and reunite with their families.

After voting at a church-adjacent poll site in an upper-class Caracas neighborhood, González called on the country’s armed forces to respect “the decision of our people.”

“What we see today are lines of joy and hope,” González, 74, told reporters. “We will change hatred for love. We will change poverty for progress. We will change corruption for honesty. We will change goodbyes for reunions.”

An April poll by Caracas-based Delphos said about a quarter of Venezuelans were thinking about emigrating if Maduro wins Sunday. The poll had a margin of error of plus or minus 2 percentage points.

Most Venezuelans who migrated over the past 11 years settled in Latin America and the Caribbean. In recent years, many began setting their sights on the U.S.

Both campaigns have distinguished themselves not only for the political movements they represent but also on how they have addressed voters' hopes and fears.

Maduro's campaign rallies featured lively electronic merengue dancing as well as speeches attacking his opponents. But after he caught heat from leftist allies such as Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva for a comment about a “bloodbath” should he lose, Maduro recoiled. His son told the Spanish newspaper El Pais that the ruling party would peacefully hand over the presidency if it loses — a rare admission of vulnerability out of step with Maduro campaign's triumphalist tone.

In contrast, the rallies of González and Machado prompted people to cry and chant “ Freedom! Freedom! ” as the duo passed by. People handed the devout Catholics rosaries, walked along highways and went through military checkpoints to reach their events. Others video-called their relatives who have migrated to let them catch a glimpse of the candidates.

“We do not want more Venezuelans leaving, and to those who have left I say that we will do everything possible to get them back here, and we will welcome them with open arms,” González said Sunday.

___

Associated Press writers Joshua Goodman and Fabiola Sánchez contributed to this report.