A jury on Thursday acquitted a Broward sheriff's deputy accused of failing to protect students during the 2018 Parkland school shooting.

Jurors deliberated for 19 hours over four days in the case of former Broward County Sheriff's Deputy Scot Peterson, who remained outside a three-story classroom building at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School during the gunman's six-minute attack on Feb. 14, 2018.

Watch NBC6 free wherever you are

>Peterson, 60, was charged with seven counts of felony child neglect for four students killed and three wounded on the 1200 building's third floor. Peterson arrived at the building with his gun drawn 73 seconds before the gunman reached that floor, but instead of entering, he backed away as gunfire sounded. He has said he didn't know where the shots were coming from.

PETERSON TRIAL

Get local news you need to know to start your day with NBC 6's News Headlines newsletter.

>Peterson was also charged with three counts of misdemeanor culpable negligence for the adults shot on the third floor, including a teacher and an adult student who died. He also faced a perjury charge for allegedly lying to investigators.

The jury Thursday acquitted Peterson of all 11 charges. Peterson broke down in tears and wept as the judge handed down the verdict.

After court adjourned, Peterson, his family and friends rushed into a group hug as they whooped, hollered and cried. One of his supporters chased after lead prosecutor Chris Killoran and said something. Killoran turned and snapped at him, “Way to be a good winner” and slapped him on the shoulder. Members of the prosecution team then nudged Killoran out of the courtroom.

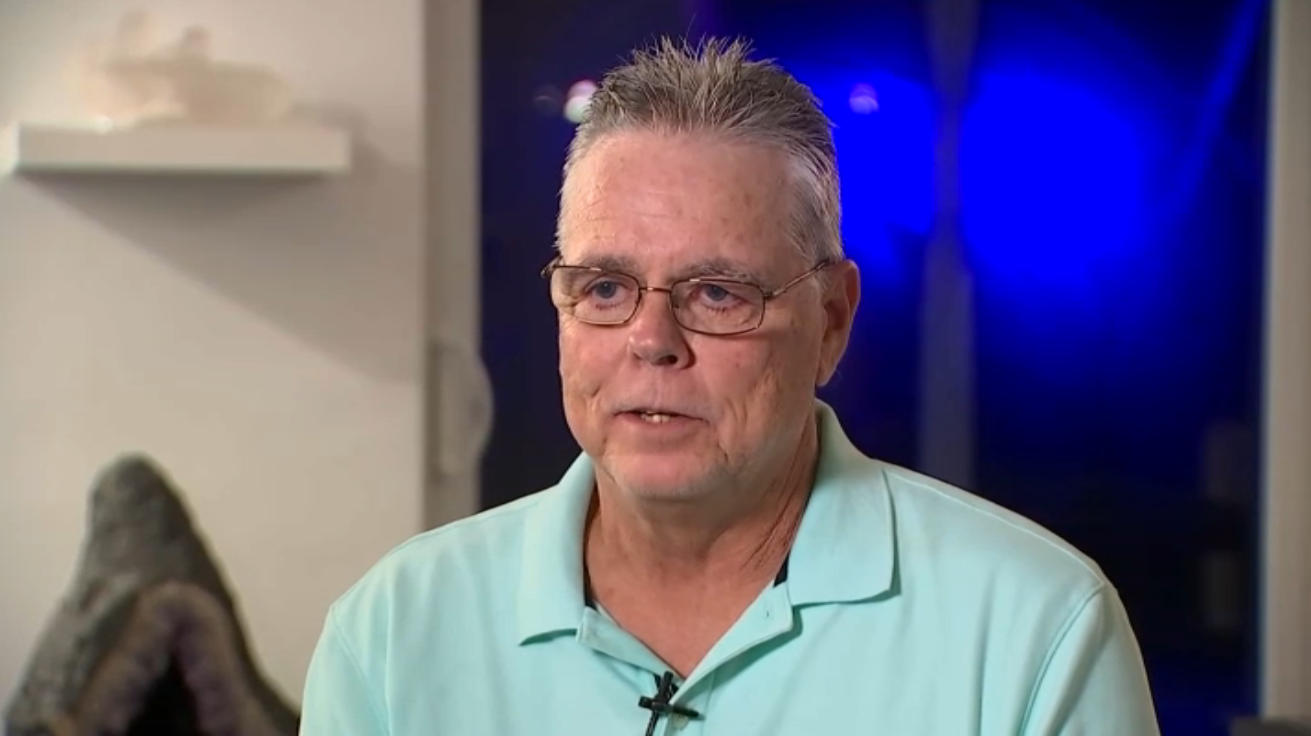

“I got my life back. We’ve got our life back,” Peterson said as he exited the courtroom, his arm around his wife, Lydia Rodriguez, and his lawyer, Mark Eiglarsh. “It’s been an emotional rollercoaster for so long. Calling Mark at 1 in the morning.”

He also said people should never forget the victims.

“Only one person was to blame and it was that monster (the shooter),” Peterson said. “It wasn’t any of the law enforcement who was on that scene. ... Everybody did the best they could with the information we had.”

Peterson said he hopes to one day sit down with the Parkland parents and spouses to tell them “the truth,” that he did everything he could.

“I would love to talk to them. I have no problem,” he said. “I’m there.”

Tony Montalto, whose daughter Gina was killed in the massacre, condemned the acquittal.

"We still feel like he (Peterson) should be haunted every day," Montalto told reporters, adding that the former deputy's inaction contributed to his daughter's death and to the shock and devastation of the community.

Peterson faced up to nearly 100 years in prison if convicted, although because of his clean record a sentence anywhere near that length was highly unlikely. He also faced losing his $104,000 annual pension. He had spent nearly three decades working at schools, including nine years at Stoneman Douglas. He retired shortly after the shooting and was then fired retroactively.

Prosecutors did not charge Peterson in connection with the 11 killed and 13 wounded on the first floor before he arrived at the building. No one was shot on the second floor.

The trial began June 7 and the jury, which includes four women and two men, began deliberations Monday after hearing closing arguments.

During their closings, prosecutors argued Peterson fled to safety during the shooting, putting his own life ahead of the children he was charged with protecting and giving the gunman time to fatally shoot several victims.

Peterson could have located and stopped the gunman, prosecutor Kristen Gomes told the jury. But instead of opening a door, looking in a window or seeking information from fleeing students, he chose to take shelter next to an adjoining building, Gomes said. That prevented him from confronting the gunman before he reached the third floor, where six of the shooter's 17 killings were committed.

Even if he hadn't killed the gunman, his presence would have distracted him, giving students and teachers time to flee or hide, or caused him to surrender or commit suicide, Gomes said.

"Choose to go in or choose to run? Scot Peterson chose to run," Gomes said. “When the defendant ran, he left behind an unrestricted killer who spent the next four minutes and 15 seconds wandering the halls at his leisure. Because when Scot Peterson ran, he left them in a building with a predator unchecked.”

But Peterson's attorney, Mark Eiglarsh, argued that Peterson was being made a "sacrificial lamb" for failures by elected officials and administrators. He said the evidence proved Peterson's insistence that the gunshots' echoes prevented him from pinpointing the gunman's location is the truth and Peterson did everything he could under the circumstances. Criticizing his actions now is "Monday morning quarterbacking" using facts that were unknown to Peterson in real time.

He said the only person responsible for what happened that day is “that monster," referring to the gunman. He said two dozen students, teachers and others testified that they also could not pinpoint where the shots were coming from — some of them from inside the building where the shooting happened.

“This whole hearing-based prosecution is flawed and offensive,” Eiglarsh said. He said Peterson acted heroically during the shooting, staying put to transmit whatever information he had and would have charged into the building if he knew where the shooter was. But if he did that or went elsewhere without solid information and the shooter then killed others where Peterson had left, he would have been prosecuted for that.

“He was damned no matter what,” Eiglarsh said.

Prosecutors, during their two-week presentation, called to the witness stand students, teachers and law enforcement officers who testified about the horror they experienced and how they knew where the gunman was. Some said they knew for certain the shots were coming from the 1200 building. Prosecutors also called a training supervisor who testified Peterson did not follow protocols for confronting an active shooter.

“As parents, we have an expectation that armed school resource officers – who are under contract to be caregivers to our children – will do their jobs when we entrust our children to them and the schools they guard,” Broward State Attorney Harold F. Pryor and the prosecutor's office said in a statement after the verdict. “They have a special role and responsibilities that exceed the role and responsibilities of a police officer. To those who have tried to make this political, I say: It is not political to expect someone to do their job.”

Eiglarsh during his two-day presentation called several deputies who arrived during the shooting and students and teachers who testified they did not think the shots were coming from the 1200 building. Peterson did not testify.

Eiglarsh also emphasized the failure of the sheriff's radio system during the attack, which limited what Peterson heard from arriving deputies. Gomes said the radio system worked well during the critical first minutes of the attack, with Peterson being the one with the best information as he was within feet of the building.