South Florida bears a history of segregation, where Black and white people were not just separated in their daily lives but also in death.

Black cemeteries are now the focus of a statewide preservation effort. NBC 6 explores how this history — once erased — is being rediscovered in our special series, "Hidden History."

Black Burial Grounds

A chain-link fence separates Lincoln Memorial Park Cemetery from the surrounding community of Brownsville.

Concrete burial vaults bear the names of prominent Black South Florida pioneers, like Miami’s first Black millionaire and the founder of Miami’s first Black-owned newspaper.

Lincoln Memorial Park Cemetery is one of a handful of surviving Black cemeteries in South Florida.

It is also a reminder of an uncomfortable truth about South Florida’s past.

Jim Crow laws and state and local laws that enforced racial segregation separated white and Black people not just in life, but also in death.

Today, Black burial grounds are more likely to be abandoned, neglected, or erased.

“The cemeteries that were identified as Black cemeteries were marginalized…they would not get the state funding to preserve them and keep them up, as compared to the white cemeteries,” Dr. Antoinette Jackson said.

Many cemeteries became victims of sprawling development at a time when racist housing policies forced Black people out of their own communities.

Jackson is the founder of the Black Cemetery Network, a group dedicated to finding and protecting Black burial grounds.

Jackson and other community members in the Tampa Bay area have been working to bring attention to the issue of erased Black cemeteries.

Residents in a Tampa public housing complex found a cemetery laid beneath their homes in 2019.

Zion Cemetery would become the first of five Black cemeteries rediscovered in the Tampa Bay area after they were built over decades ago.

“We are uncovering the injustices of these cemeteries that are from the past, pushing for reparations if necessary, whether they are markers, memorials,” said Walter Jennings with the Black Cemetery Network.

At the state level, a task force made up of lawmakers and experts is looking at what to do when these cemeteries are found.

“What does making this right look like for our community,” State Rep. Fentrice Driskell said. “It’s a statewide issue and there needs to be some resources dedicated to it, it is simply the right thing to do.”

Florida House Bill 1215, if passed, would create a state agency to help find, research, and preserve these historic sites.

It’s unclear if the legislation would do much to help a privately owned cemetery like Lincoln Memorial Park Cemetery.

“We cleaned the nameplate off, and that’s how I was able to find her here. It was the first time in my life finding my mother,” Jessie Wooden said.

Wooden came to Lincoln Memorial Park Cemetery in hopes of locating his mother’s final resting place.

Instead, he found a cemetery in disrepair.

“It wasn’t to my liking for my mother to be kept,” Wooden said.

Over the years, financial troubles and a lack of maintenance resulted in hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines from the county. The previous owner made the decision to sell the cemetery to Wooden.

“I didn’t know this place was a legacy, I didn’t know this place was historical," Wooden said, "These iconic people out here and the way they are being kept, and the way this place was being run, I was taken aback."

Wooden has been working to fix the place up since he purchased it in 2020.

“I came for my mother, to make sure she was taken care of,” Wooden said.

Jessie hopes to build partnerships with community organizations and the county in order to preserve Lincoln Memorial Park Cemetery.

Though Lincoln Memorial Park has suffered periods of neglect, it’s still visible and operating.

Labor of Love

“It’s very important that we know our history so we will know who we are,” Dr. Enid Pinkney said.

Pinkney is the driving force behind preserving one of Miami’s most iconic Black historic sites.

The Historic Hampton House is one of Miami’s only remaining Green Book motels. It served as a safe haven for Black travelers during segregation.

Pinkney is also known for her work preserving an erased Black burial ground in Lemon City.

“Those people were buried in the Lemon City Cemetery and they didn’t ask you to dig them up,” Pinkney said.

In 2009, construction crews unearthed human remains in an area of Little Haiti previously known as Lemon City.

Maps from the 1930s show a cemetery once stood on the property. This evidence did little to keep the site from being developed in the decades to come.

Pinkney and other advocates helped stop a planned redevelopment of the area when the site was rediscovered.

“After I got official proof that this was a cemetery, we said, no, it’s not right, you can’t build, you are disrespecting the dead, that is not right,” Pinkney said.

Today, a monument marks the cemetery and lists more than 500 names of those buried.

“John Clark, my grandfather’s name was John Clark,” Pinkney pointed out.

While working to preserve the site, Pinkney learned her grandfather was one of the people buried in Lemon City Cemetery.

“Why would this site not be recognized?” Dr. Alisha Winn said.

Winn is an applied cultural anthropologist. She says the push to identify and mark Black burial grounds helps to safeguard an accurate account of the past.

“Those in power can decide what history is, and you can erase it, you can silence it, and not talk about it if you choose to,” Winn said.

She took NBC 6 to a park in West Palm Beach, the final resting place to 674 mostly Black migrant farmworkers killed when a catastrophic storm hit South Florida in 1928.

“They were brought here on dump trucks,” Winn explained.

The storm victims were buried in a mass grave.

The unmarked property, according to public records, would later become a part of a land exchange by the City of West Palm Beach. At that time, the mass gravesite was not disclosed. The property faded from public view.

In the 1990s, Dorothy Hazard and her husband helped lead an effort to get the site marked.

“The county and the city needed to do more in order to get this site and other sites that are unrecognized or not taken care of, better,” Hazard said.

Historic markers were finally placed at the site 75 years after the mass burial.

The Storm of ’28 Memorial Park Coalition, Inc., has continued to fight for the site’s preservation.

The site is currently owned and maintained by the City of West Palm Beach. A spokesperson for the city of West Palm Beach told NBC 6 in a statement, “The city partners with the Storm of ’28 Memorial Park Coalition to ensure the lives of those buried at the site are never forgotten. Funded by the city, the West Palm Beach Community Redevelopment Agency provides funding assistance to the coalition to produce an annual remembrance ceremony. The city and its leadership actively support and participate in events in memory of the individuals who are buried there.”

Hidden in Plain Sight

Reckoning America’s past could mean uncovering what’s beneath the places we drive past or visit daily.

“As you delved deeper into the stories of what happened, with these cemeteries and these gravesites, sometimes it was far more intentional, far more egregious. Some of these were intentionally stolen, they were desecrated, they were built on top of,” State Rep. Fentrice Driskell said.

Driskell is pushing for the protection and preservation of these sites.

But to protect Black burial grounds, you have to locate them first.

“Right now I don’t think there is any acknowledgment that there are Black people buried under there,” Dr. Marvin Dunn said.

Local historian and author Dr. Marvin Dunn says there is reason to believe a Black cemetery was erased in the Allapattah area of Miami.

A Miami-Dade Public School parking lot, City of Miami park, and fire station currently sit in this community three blocks off of NW 46th Street.

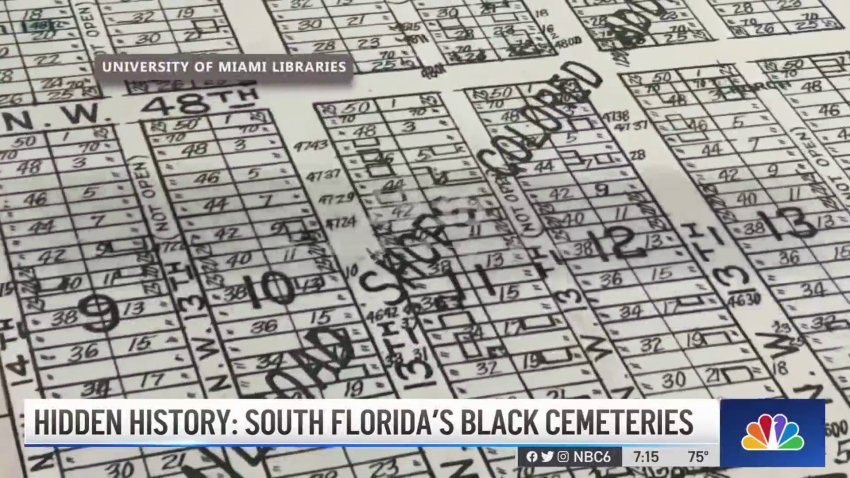

A map from 1936 shows it was once a Black community called Railroad Shop Colored Addition.

“It used to be Railroad Shop Colored Addition. This used to be a Black community, pretty much intact that developed here for people who worked repairing the railroad, trains,” Dunn said.

It’s a place Kenneth Kilpatrick has heard about for years.

“My family was among other families who lived and worked the railroads,” Kilpatrick said.

He introduced his dad and aunt, who were born and lived in the Railroad Shop Community as children.

Their house would have sat directly in front of what is now Charles Hadley Park.

“I remember I was crying, it was raining, it was raining real hard,” his aunt Geraldine Owens said.

She does not remember a cemetery being in the community, but she does remember being forced out of her home in 1947 when the City of Miami seized the property of Black residents.

“I just remember being really frightened and really, really scared that they were going to do something to my grandfather,” Owens said.

After the families were forcibly evicted, the property was used to build a school for white children.

The school is now named after the late Railroad Shop activist Georgia Jones-Ayers. Jones-Ayers was a teenager at the time of the evictions.

Dunn says she told him about the existence of a cemetery here before her passing.

“She knew it to be there when she was a little girl, I trust Georgia’s word,” Dunn said.

We wanted to know what Miami-Dade County Public Schools knew about the property. A spokesperson shared a 1948 land survey and aerial photos from 1957. In an email, the spokesperson told us, “to the best of our knowledge and after looking at the documents we were able to find, there were no notes indicating an existing cemetery.”

There also isn’t any reference to a cemetery on the 1936 map we found of the community.

But oral histories, some of which have been printed in newspapers, suggest a cemetery could have predated the Railroad Shop Community.

Local genealogist Larry Wiggins helped in the rediscovery of Lemon City Cemetery.

He pointed us to a 2006 article in The Miami Herald, which chronicles interviews from old-time Black Miamians. One woman remembered one place black families "could buy parcels was the site of a Black burial ground, Evergreen Cemetery.” The cemetery was reportedly relocated and the land reportedly would become a part of the Railroad Shop Colored Addition.

We also found this 1920 newspaper clipping from The Miami News which offers another clue. It makes reference to an Evergreen Colored Cemetery near the Railroad Shop Colored Addition which offered to sell acres of land. We do not know what came of this offer.

A historically Black burial ground known as Evergreen Memorial Park Cemetery still exists today in Brownsville.

We reached out to the current owner of the property to find out if they have any information that could point to whether the cemetery was ever relocated or if graves from Allapattah were moved to the cemetery. We are still waiting to hear back.

We do not know what came of the colored cemetery to the north mentioned in the article. However, it was not uncommon for the bodies of Black people to be relocated.

A 1916 birth certificate shows a baby, originally buried in an Evergreen Cemetery, was later relocated to another Black burial ground.

It is unclear if an erased cemetery still remains in the Allapattah, but Dunn believes one does.

“It’s a parking lot, but it is sacred ground, that is hurtful to me,” Dunn said.

We asked Miami-Dade Public Schools if they ever used technology to detect the presence of possible graves at the site. They said they have not.

We also reached out to the City of Miami but are yet to hear back.