As South Florida comes to grips with an opioid epidemic, many who've been down the path to heroin addiction recall the same first step: abuse of prescription pain killers.

"It’s the same pattern with almost 99 percent of the people we see here," said Marc Romano, director of medical services for Delphi Behavioral Health, which owns Ocean Breeze Recovery in Pompano Beach. "They start out with the prescription pain pills and then they move to heroin because it's easier to get and cheaper."

It wasn’t always that way.

South Florida was once home to a booming — though illegal — market in prescription opioids, such as Vicodin, Percocet and Oxycontin.

A crackdown on the so-called pill mills beginning about seven years ago led to dozens of arrests of doctors and clinic owners.

And its success in stemming the flow of pharmaceutical opiates was felt all along the eastern United States.

In rural Connecticut, 15-year-old Britney Cornelison was bored and hanging with a risky crowd when she first tried OxyContin because “that’s what was going around at the time.”

Local

"I kind of just escaped," she said. "It was a nice way to let go for a while."

And then it wasn’t.

"It definitely turned bad very fast," she recalled.

As supplies of pills dwindled and prices soared, she turned to heroin at age 19.

"It was just stronger. You didn’t need as much of it to get where you wanted to get," she said. "That’s what it was really about for me was the effect. It was just how much more messed up I could get."

Eventually, she landed in rehab at Ocean Breeze, where now — age 24 and clean more than two years — she is a case manager.

At her side at times, Matt Danner, once a commercial fisherman in New England, until his addiction led him to Ocean Breeze, where he’s now an admissions coordinator.

He tried OxyContin around 2002.

"Everybody always had it,” he recalled. “They were cheap, but I saw the price go from $50 a pill to $60 to $70 to eventually $80 a pill. You’re doing two pills, three pills a day, it becomes harder to support your habit."

Next came heroin.

"For about $20 for the day I was as high as I would’ve been off of $200 worth of pills," he said.

Romano and Ocean Breeze’s program helped both Cornelison and Danner, 32, reclaim their lives.

But Romano, a psychologist, says a steady stream of young addicts keep arriving at his door on Atlantic Boulevard, an area once at the heart of Broward’s pill mill heyday.

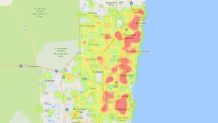

A map of opioid overdoses prepared by the county reveals 24 deaths last year within a mile of the Ocean Breeze offices.

NBC 6 Investigators used the data behind county map to create another that highlights where deaths are concentrated: nine, for instance, in or around just two low-budget motels near the Turnpike and Coconut Creek Parkway.

Another two dozen within a mile of Old Dixie Highway and Sample Road — the very same intersection where a pill mill once stood.

"They cracked down on it, but the individuals with addictions are still here,” Romano said. “They had to get that fix somewhere and what they did is they turned to cheaper, more available heroin.”

Heroin that is now sometimes laced with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 10 times stronger than heroin, or carfentanyl, which is 10 times stronger than that.

That potency is driving the surge in opioid deaths in Miami-Dade and Broward, medical examiners' office records show.

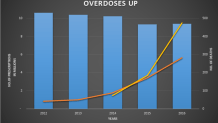

Last year, the two counties reported heroin was present in or the cause of 282 deaths, compared to just 18 in 2011 — a 15-fold increase.

Fentanyl, which was reported separately in deaths beginning in 2014, was found in 474 deaths in the two counties last year — up from just 75 in 2014.

And the NBC 6 Investigators found while those opioid-death numbers soar, the number of prescriptions for opioids in the state is decreasing.

A state database of prescriptions shows doctors wrote more than 1.2 million fewer prescriptions for hydrocodone and oxycodone in the year ending June 2016 than they did four years earlier.

When shown the research, Romano said a causal relationship between fewer pills and more heroin deaths would be a reasonable inference.

"People are not getting access to prescription pills, which are probably a little safer if you will, because you know what you’re getting," he said. "We got all these people hooked on prescription pain pills, opiates, then we took it away, but they still need something."

The answer, of course, is not to go back to the days when pill mills handed out drugs like candy to anyone who claimed to be sick.

Physicians being more careful in how they prescribe the drugs, with a goal of preventing addiction, is one key step, he said.

But once addicted, users can seek treatment that replaces heroin with other drugs that, over weeks, lessen that effects of opiate withdrawal, as they then transition into therapies designed to help them maintain sobriety.

Or at least try to.

Romano has seen his share of relapses and deaths.

"This is something people have a profound drive to get and nothing will getting their way," he said, recalling asking one woman why she kept returning to heroin. "Her response was, 'I'm in love with heroin.' Not 'I love doing it. I love the effects.' But, 'I’m in love with it.' And then she added, 'If I could marry it, I would.'"