What to Know

- The gunman responsible for the Feb. 14, 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School pleaded guilty to all the charges against him Wednesday

- Nikolas Cruz entered the plea on 17 counts of first-degree murder and 17 counts of attempted first-degree murder

- Cruz, now 23, was sentenced to 26 years in prison for an attack on a jail guard nine months after the shooting

Over three years after the mass shooting that took the lives of 17 students and staff inside a Parkland high school, the man who confessed to pulling the trigger pleaded guilty in a Broward County courtroom Wednesday.

Nikolas Cruz entered the plea on 17 counts of first-degree murder and 17 counts of attempted first-degree murder for the February 14, 2018 tragedy at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

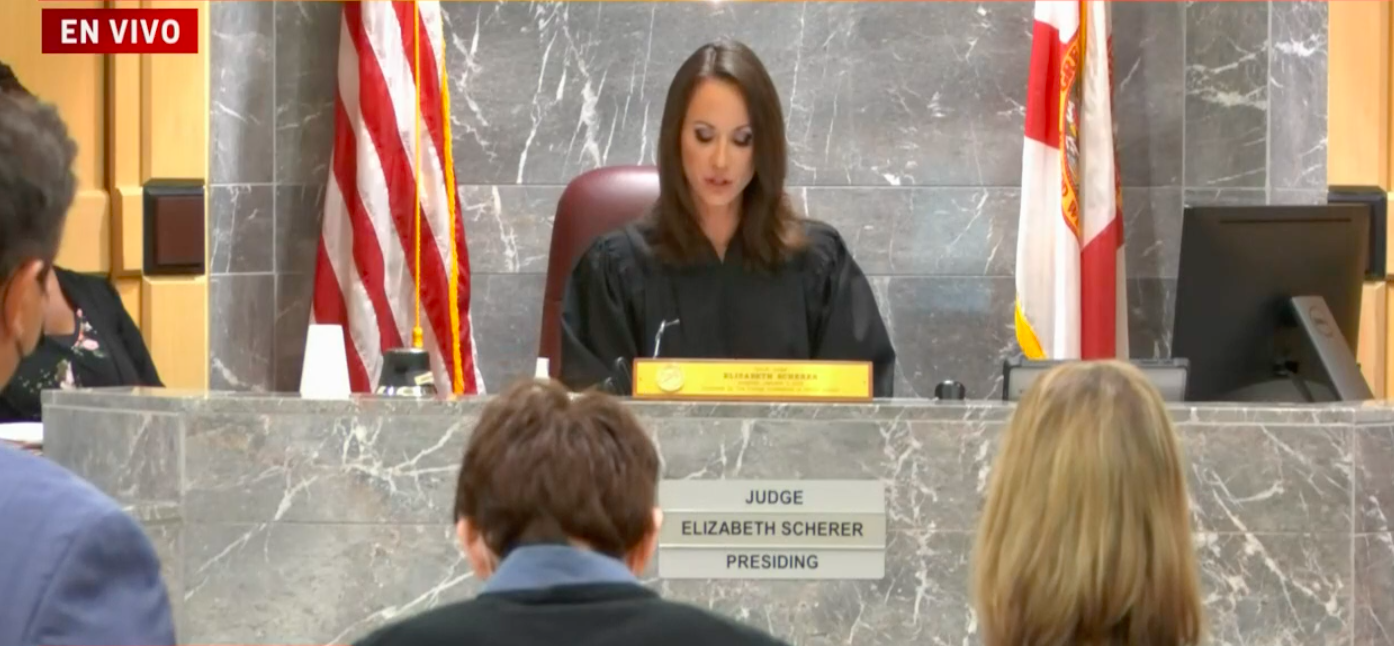

Cruz, 23, entered his pleas in a courtroom attended by a dozen relatives of victims after answering a long list of questions from Circuit Judge Elizabeth Scherer aimed at confirming his mental competency.

The Hurricane season is on. Our meteorologists are ready. Sign up for the NBC 6 Weather newsletter to get the latest forecast in your inbox.

PARKLAND SCHOOL TRAGEDY

Scherer later allowed Cruz to make a statement, which he used to apologize to the families of the victims.

"I am very sorry for what I did and I have to live with it every day and that if I were to get a second chance, I will do everything in my power to try to help others," Cruz said, as several parents shook their heads. "And I am doing this for you and I do not care if you do not believe me and I love you and I know you don't believe me. I have to live with this every day and it brings me nightmares and I can't live with myself sometimes but I try to push through because I know that's what you guys would want me to do."

Cruz also added that he wished it was up to the survivors to determine whether he lived or died.

"I'm trying my best to maintain my composure and I just want you to know that I'm really sorry and I hope you give me a chance to try to help others," he said. "I believe it's your decision to decide where I go, whether I live or die, not the jury's, I believe it's your decision. I'm sorry."

Parents scoffed at Cruz’s statement as they left the courtroom, saying it seemed self-serving and aimed at eliciting unearned sympathy. Gena Hoyer, whose 15-year-old son Luke died in the shooting, saw it as part of a defense strategy “to keep a violent, evil person off death row."

She said her son was “a sweet young man who had a life ahead of him and the person you saw in there today chose to take his life. He does not deserve life in prison.”

Several parents and other relatives of victims broke down in tears while listening to the court proceedings via a Zoom call. At one point, former Broward County State Attorney Michael Satz detailed the events of the shooting from when Cruz arrived at the school to when he shot his last victim and was later captured.

The guilty plea sets up a penalty phase where Cruz will be fighting against the death penalty and hoping for life without parole. Scherer said jury selection is scheduled to begin in January.

Cruz attorney David Wheeler told Scherer about his intent to plead guilty in the shooting during a hearing last Friday, where Cruz entered a guilty plea to attacking a jail guard nine months after the shooting.

During Wednesday's hearing, Scherer sentenced Cruz to 26 years in prison on the four charges related to the jail guard attack.

Cruz said he understood that prosecutors can use the conviction as an aggravating factor when they later argue for his execution.

The trial has been delayed by the pandemic and arguments over what evidence could be presented to the jury, frustrating some victims' families and the wounded.

Samantha Grady, who was injured in the massacre and lost her best friend, 17-year-old Helena Ramsay, said she is glad Cruz is finally acknowledging the damage he caused.

“I hope we can start the process of truly moving on,” she said. “His punishment should be equal to the lives he has taken, the stress and horrors he has caused in a whole community, a whole state."

Debbie Hixon, who lost her husband — athletic director Chris Hixon — navigated this pivotal moment ahead of the plea Wednesday.

"As families, because we’ve been in a holding pattern, there are stages of grief and we’re still in the first stage of anger even this far down the line because there has just been no inkling that justice is ever going to be served," Hixon said. "I think for us it’s a way to move forward."

In the aftermath of the shooting, Parkland student activists formed March for Our Lives, a group that rallied hundreds of thousands around the country for tighter gun laws, including a nationally televised march in Washington, D.C.

Cruz and his lawyers had long offered to plead guilty to the shooting in exchange for a life sentence, but prosecutors had rejected that deal.

Attorney David Weinstein, a former Florida prosecutor who is not involved in the case, said by pleading guilty to the murder charges, Cruz's lawyers will be able to tell the jury in the penalty hearing that he “has accepted responsibility, has shown remorse and saved the victim’s families the additional trauma of a guilt phase trial.”

The jurors also won’t repeatedly see the security videos that reportedly captured the shooting in graphic detail. Their goal will be to persuade one juror to vote for a life sentence — unanimity will be required to sentence Cruz to death.

Cruz’s rampage crushed the veneer of safety in Parkland, an upper-middle-class community with little crime. Cruz was a longtime, but troubled resident.

Broward Sheriff’s deputies were frequently called to the home in an upscale neighborhood he shared with his widowed mother and younger brother for disturbances, but they said nothing was ever reported that could have led to his arrest.

Cruz alternated between traditional schools and those for troubled students.

He attended MSD starting in 10th grade, but his troubles remained — at one point, he was prohibited from carrying a backpack to make sure he didn’t carry a weapon. Still, he was allowed to participate on the school’s rifle team.

He was expelled about a year before the attack after numerous incidents of unusual behavior and at least one fight. He then began posting videos online in which he threatened to commit violence, including at the school.

When Cruz’s mother died of pneumonia four months before the shooting, he began staying with friends, taking his 10 guns with him.

Someone worried about his emotional state called the FBI a month before the shooting to warn agents he might kill people. The information was never forwarded to the agency’s South Florida office.

Another acquaintance called the Broward Sheriff’s Office with a similar warning, but when the deputy learned Cruz was then living with a family friend in neighboring Palm Beach County he told the caller to contact that sheriff’s office.

In the weeks before the shooting, Cruz began making videos proclaiming he was going to be the “next school shooter of 2018.”

The shooting happened on Valentine’s Day. Students had exchanged gifts and many were dressed in red.

Cruz, then 19, arrived at the campus that afternoon in an Uber, assembled his rifle in a stairwell and then opened fire in the three-story classroom building.

Cruz eventually dropped his rifle and fled, blending in with his victims as police stormed the building. He was captured about an hour later walking through a residential neighborhood.

The shooting led to a state law that requires all Florida public schools to have an armed guard on campus during class hours.

Hixon, now a member of Broward's school board who has now devoted her time to safer schools, also wants the focus to be on the victims.

"What’s important is what we lost and how do we move forward. He is not important," Hixon said.