China moved to lock down at least three cities with a combined population of more than 18 million in an unprecedented effort to contain the deadly new virus that has sickened hundreds of people and spread to other parts of the world during the busy Lunar New Year holiday.

The open-ended lockdowns are unmatched in size, embracing more people than New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago put together.

The train station and airport in Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak, were shut down, and ferry, subway and bus service was halted. Normally bustling streets, shopping malls, restaurants and other public spaces in the city of 11 million were eerily quiet. Police checked all incoming vehicles but did not close off the roads.

Similar measures were being imposed Friday in the nearby cities of Huanggang and Ezhou. In Huanggang, theaters, internet cafes and other entertainment centers were also ordered closed.

In the capital, Beijing, major events were canceled indefinitely, including traditional temple fairs that are a staple of holiday celebrations, to stop the spread of the virus. The Forbidden City, the palace complex in Beijing that is now a museum, announced it will close indefinitely on Saturday.

China's National Health Commission said Friday morning the confirmed cases of the new coronavirus had risen to 830 with 25 deaths. The first death was also confirmed outside the central province of Hubei, where the capital, Wuhan, has been the epicenter of the outbreak. The health commission in Hebei, a northern province bordering Beijing, said an 80-year-old man died after returning from a two-month stay in Wuhan to see relatives.

The vast majority of cases have been in and around Wuhan or people with connections the city. Other cases have been confirmed in the United States, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea and Thailand. Singapore and Vietnam reported their first cases Thursday, and cases have also been confirmed in the Chinese territories of Hong Kong and Macao.

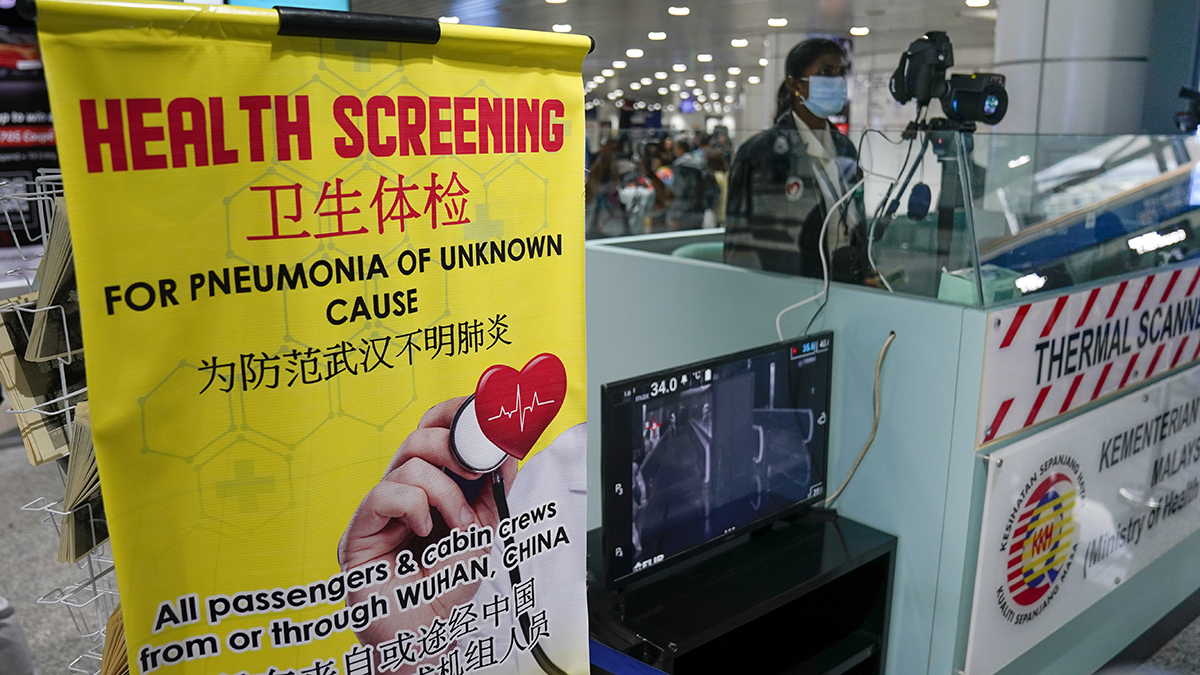

Many countries are screening travelers from China for symptoms of the virus, which can cause fever, coughing, breathing difficulties and pneumonia.

The World Health Organization has decided against declaring the outbreak a global emergency, a step that can bring more money and resources to fight a threat but that can also cause trade and travel restrictions and other economic damage, making the decision a politically fraught one.

The decision “should not be taken as a sign that WHO does not think the situation is serious or that we’re not taking it seriously. Nothing could be further from the truth,” WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said. “WHO is following this outbreak every minute of every day.”

The U.N. health agency defines a global emergency as an “extraordinary event” that constitutes a risk to other countries and requires a coordinated international response.

A declaration of a global emergency typically brings greater money and resources, but may also prompt nervous governments to restrict travel and trade to affected countries. The announcement also imposes more disease-reporting requirements on countries.

But declaring an international emergency can also be politically fraught. Countries typically resist the notion that they have a crisis within their borders and may argue strenuously for other control measures.

Chinese officials have not said how long the shutdowns of the cities will last. While sweeping measures are typical of China's Communist Party-led government, large-scale quarantines are rare around the world, even in deadly epidemics, because of concerns about infringing on people's liberties. And the effectiveness of such measures is unclear.

“To my knowledge, trying to contain a city of 11 million people is new to science," said Gauden Galea, the WHO''s representative in China. “It has not been tried before as a public health measure. We cannot at this stage say it will or it will not work."

Jonathan Ball, a professor of virology at molecular virology at the University of Nottingham in Britain, said the lockdowns appear to be justified scientifically.

“Until there's a better understanding of what the situation is, I think it's not an unreasonable thing to do,” he said. “Anything that limits people's travels during an outbreak would obviously work.”

But Ball cautioned that any such quarantine should be strictly time-limited. He added: “You have to make sure you communicate effectively about why this is being done. Otherwise you will lose the goodwill of the people.”

During the devastating West Africa Ebola outbreak in 2014, Sierra Leone imposed a national three-day quarantine as health workers went door to door, searching for hidden cases. Burial teams collecting corpses and people taking the sick to Ebola centers were the only ones allowed to move freely. Frustrated residents complained of food shortages.

In China, the illnesses from the newly identified coronavirus first appeared last month in Wuhan, an industrial and transportation hub. Local authorities demanded all residents wear masks in public places and urged civil servants wear them at work.

After the city was closed off Thursday, images showed long lines and empty shelves at supermarkets, as people stocked up. Trucks carrying supplies into the city are not being restricted, although many Chinese recall shortages in the years before the country's recent economic boom.

Analysts predicted cases will continue to multiply, although the jump in numbers is also attributable in part to increased monitoring.

“Even if (cases) are in the thousands, this would not surprise us," the WHO's Galea said, adding, however, that the number of infected is not an indicator of the outbreak's severity so long as the death rate remains low.

The coronavirus family includes the common cold as well as viruses that cause more serious illnesses, such as the SARS outbreak that spread from China to more than a dozen countries in 2002-03 and killed about 800 people, and Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome, or MERS, which is thought to have originated from camels.

China is keen to avoid repeating mistakes with its handling of SARS. For months, even after the illness had spread around the world, China parked patients in hotels and drove them around in ambulances to conceal the true number of cases and avoid WHO experts. This time, China has been credited with sharing information rapidly, and President Xi Jinping has emphasized that as a priority.

Health authorities are taking extraordinary measures to prevent the spread of the virus, placing those believed infected in plastic tubes and wheeled boxes, with air passed through filters.

The first cases in the Wuhan outbreak were connected to people who worked at or visited a seafood market, now closed for an investigation. Experts suspect that the virus was first transmitted from wild animals but that it may also be mutating. Mutations can make it deadlier or more contagious.

Associated Press journalists Shanshan Wang, Shanghai, Maria Cheng and Krista Larson contributed to this report.